During our video call, fantasy author Nghi Vo tells me that she plans to hug her cat a lot before she goes off on a book tour again. I’ve been trying to not latch onto the gray cat lounging in the background of Vo’s screen. I coo at the cat, while she tsk-tsks, but the feline continues to ignore us humans as we talk. We discuss our Vietnamese American upbringings, Vo’s 2021 debut Jazz Age fantasy novel The Chosen and the Beautiful—which reimagines The Great Gatsby through the eyes of a magical queer Vietnamese American adoptee, its follow-up novella Don’t Sleep With the Dead (released on last month), and the nuanced invisibility and visibility of Vo’s Asian American heroines.

Vo describes growing up in Peoria, Illinois as being “one in four Vietnamese families,” around “a lot of fields and corn, a lot of places to be myself ’cause I was alone.” She’s shocked when I, a Vietnamese American from Houston, mention my experience of elementary school faculty hassling me with, “So are you related to this (insert name of unrelated Asian kid)?”—although Vo does depict this brand of Asian American experience in The Chosen and the Beautiful. “In Houston (a diverse city compared to mine)? That’s unforgivable!” she says, never having encountered that kind of experience. We do both relate to the fact that our Vietnamese parents came to the United States with little awareness of its long history of anti-Asian policies, so Vo found herself struck by her Chinese American college friends attesting to their families’ long generational memory of the Chinese Exclusion Act, which inspired the fictional Manchester Act in The Chosen and the Beautiful.

Vo says she didn’t set out to become an author, “(the career) found me.” She found gigs working in tech support, at the library, and as phone sex operator, and then she landed copywriting article gigs with titles like “Why You Shouldn’t Ride Bears” and “What Flowers Grow in Zone Five.” Her first short story, Gift of Flight, debuted in 2007 and Vo implores me to forgive—what she feels are—dated “rookie mistakes” in the story. “I do see places where I could have gone deeper, pushed harder (such as) the diasporic experience of the narrator’s mother, there’s the narrator’s relationship with her father, explored in its actuality or in its absence,” she reflects.

Nghi Vo grew up in Peoria, Illinois around very few Asians.

Courtesy of Nghi Vo

She didn’t expect to reimagine F. Scott Fitzgerald’s 1925 The Great Gatsby—deemed a “Great American Novel,” and compulsively assigned as reading material in American high schools—for her debut novel, but Fitzgerald’s grand language has resided in her brain since she was about 14 years old. At the time, narrowly avoiding getting hit by a car—which parallels the vehicular manslaughter in Gatsby’s third act—fueled her obsession. But most of all, Vo nursed a literary crush on the alluring Jordan Baker, the love interest of narrator Nick Carraway, and friend of Daisy Buchanan, Nick’s unhappily married old money cousin. Vo was intrigued by Jordan’s role in reuniting Daisy with her old beau, new money millionaire Jay Gatsby, who acquired his wealth through unscrupulous means.

Deeper readings by modern readers and scholars often find Fitzgerald’s characters, Jordan and Nick in particular, to be queer coded. In a time when queer representation in books was scarce for a young Vo, she was attracted to Jordan’s queer coding, despite lacking the language then to articulate it. “I do not know if (Fitzgerald was) actively hinting that she was a lesbian,” she says. “I do wonder if she was based on queer women that he knew.” The Chosen and the Beautiful also leans into the common queer readings of Nick being romantically infatuated with Gatsby—and Gatsby himself isn’t spared from Vo’s explicit queerification either.

Vo’s reimagining of Jordan as a queer Vietnamese woman adopted by rich white folks blossomed in a pitch session, thanks to Vo’s agent being adept at “Yes and-ing,” and developing her ideas. She also bestowed her literary crush the Asiatic art of “paper cutting” magic, while digging into Jordan’s positionality—othered as a heathen, yet raised with more privilege and mobility than most Asian Americans of her time. Not an adoptee herself, Vo wrote with awareness that her depiction would not align with the complex array of adoptee experiences. Her expression is serious when she mentions, “I have read some people who feel like I got things right. I have read some people who feel that I’ve got things wrong.”

“(Writing Jordan’s adoptee) experience is…” Vo clicks her tongue and pauses to formulate her thoughts before continuing, “true to the experience of people that I care about.” When researching and writing other experiences she doesn’t embody—whether it’s the experience of the Asian American adoptees or a character based on Black actress and singer/songwriter Hattie McDaniel in her 2021 Siren Queen—she says, “I will never be perfect, but I should always be doing my best, and that’s what I expect for myself.”

Jordan isn’t the only Fitzgerald player whose race has been reimagined. Prior to writing the book, Vo was exposed to the literary speculation of the mysterious Gatsby being a white-passing Black man. So Chosen and the Beautiful reimagines him with Black and Chippewa parentage, which remains a character intrigue in Don’t Sleep with the Dead. Vo also isn’t the only writer who has switched up the identities of Fitzgerald’s characters. Her face lights up when I bring up the subject of Broadway musicals and other theater mediums adapting The Great Gatsby—from colorblind casting (like Eva Noblezada as Daisy in the recent Broadway musical), to purposeful racial and queer reimaging (reportedly the Boston-premiered Gatsby: An American Myth).

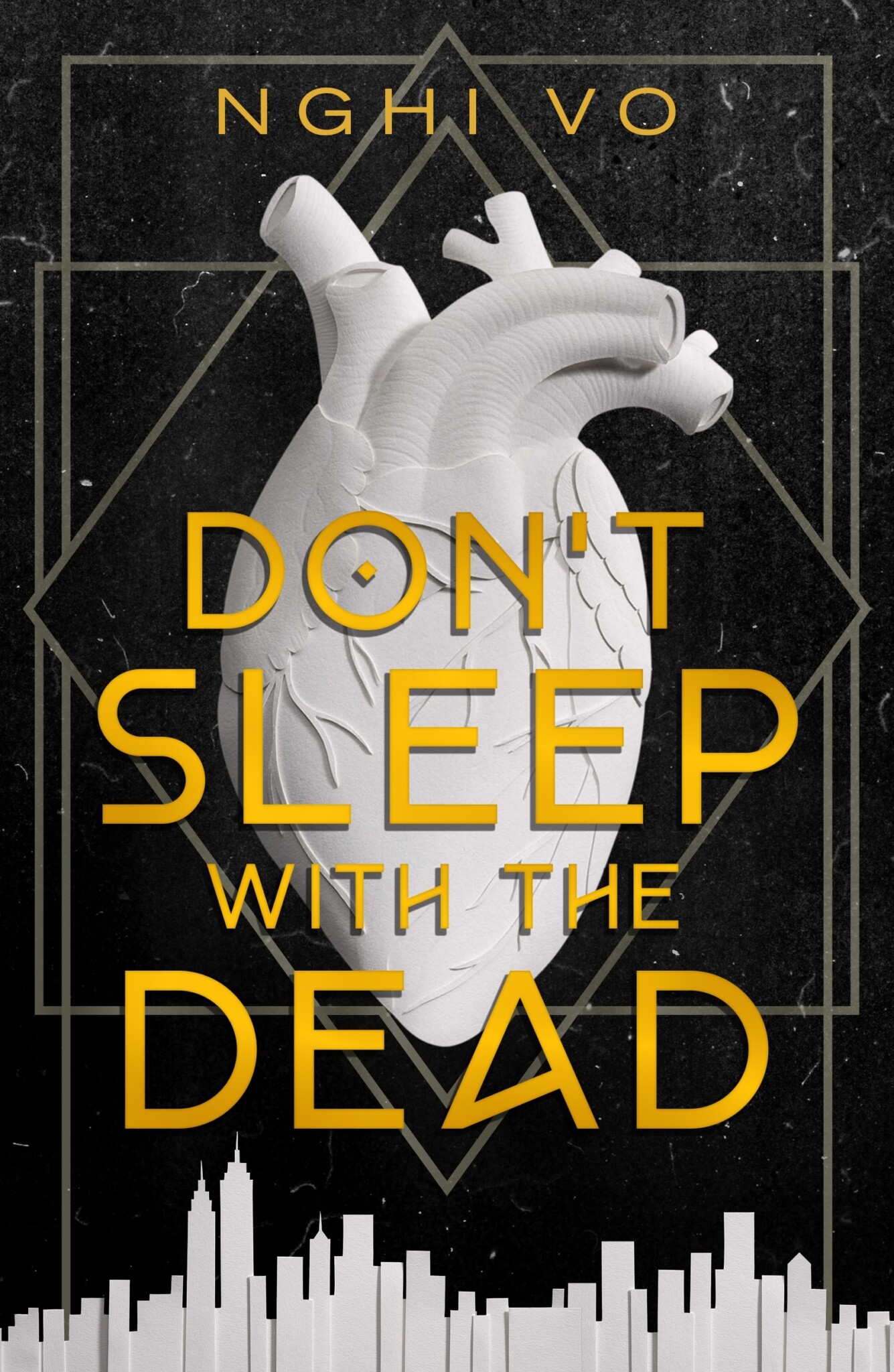

Cover for “Don’t Sleep With the Dead.”

Courtesy of Nghi Vo

In the universe of The Chosen and the Beautiful, Vo also added a small dimension to Nick’s background—a Bangkok-born great-grandmother, described as “adopted or stolen just as Jordan had been,” with Nick’s heritage so distant that, in Vo’s words, “it’s allowed to be a smaller part of (his) identity” in comparison to Gatsby’s and Jordan’s. His great-grandmother performs paper magic, and without spoiling much, it plays a role in Don’t Sleep With the Dead, creating copies of people and bringing up the questions of reinvented identities.

Vo didn’t plan her Nick Carraway follow-up while constructing Jordan’s narrative world, but the author’s penchant for volatile relationships, Nick’s infatuation with Gatsby in this case, developed the story. “(The title itself), it’s very good advice (Nick) doesn’t take.”

This longing, the wistful and obsessive, pervades Vo’s other books, including a volatile centuries-long love story between an angel and demon in The City of Glass (2024). In Vo’s Siren Queen, her Chinese American protagonist, Luli Wei, faces merciless Hollywood executives pigeonholing her into a stereotypical monster role (inspired by the trials and tribulations Anna May Wong faced) while she pines for her clandestine lesbian lover. “The weird power of invisibility, its protection, is a thing that marginalized people go through,” Vo says, finding this nuance in Luli and Jordan’s coming-of-age. “We inherited some dark gifts from the history of America.”

Speaking of this country’s dark gifts, Vo is writing a project related to the Gilded Age (that’s all she can tell me) and her agent prepped her by making her watch The Gilded Age on Max. Maybe there’s yet another “Great American Novel” for her to tackle.